Jake

Jake was a Fourth of July dog. After the Kiwanis-Sycamore Parade I found him with his sibling puppies in the back of an old pickup. They were soaking wet playing in a child size plastic pool with enough water for them to splash. Around us was the busiest day of the year for Sycamore. People, and booths were everywhere, like a blown-up version of a farmer’s market. There was a joy about the puppies I wanted to share. Will and I had just walked from the Hartz Bar downtown to the Livery after the parade to get his truck. We had plans to meet up with Erica and her friends. I know I had a good buzz on when the dogs caught my eye maybe twenty feet away.

“Dude, let’s go check out the pups.”

“No.”

“Why not?”

“As soon as we go over there, we’ll want to take one home.”

“Would that be so bad?”

“I can’t have a dog.”

“What about me?” I was living with him in one of his father’s home rentals. We lived with two roommates, and two cats. Mooch was mine, and Hobbs was his. “You think your dad would be cool if I got a dog?”

“If you want to, go ahead.”

“Yeah, but what about your dad?”

“He’ll be fine with it.”

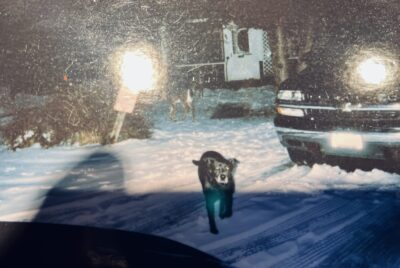

I left him. Leaning over the gate I could have watched those pups play forever. Then one put his front legs on the tailgate in front of me. He was beautiful with a short snout, big floppy ears, and thick legs and paws. You could see that this eight-week puppy would be big. Jake lived well at ninety pounds. I picked him up. He went right for my face and licked my chin. He was not free. Ten bucks said the owner. Like the dumb twenty-year-old I was then, I had spent all my money at the bar. Will and I agree that I borrowed the money from him. We disagree in that he says I didn’t pay him back, and because of that, Jake should have been his dog.

The energetic labrador/retriever mix squirmed in my lap while Will drove us to meet up with Erica and her friends. They were at Cindy’s parents’ house. They had a pool. I was a little worried about Erica’s reaction. After getting my cat, Mooch, without her input I promised Erica, I wouldn’t do it again. Of course, she fell in love with Jake immediately. If he wasn’t jumping into the pool, he sipped from the top of our beer cans poolside.

A month short of our first wedding anniversary, Erica, Jake, and I spent eight weeks on the road. We traveled the country during the summer of 1993 looking for a better place than California to live. I don’t remember the number of miles we drove, but we experienced twenty-five states on that adventure. In Washington DC, he enjoyed a leisurely, spa treatment visit while Erica and I endured a hell we still talk about.

How naïve were we to show up at a dog kennel the Thursday before the Fourth of July on Sunday? In the parking lot we waited for a kennel to open. The first said no. The second seemed sympathetic to our dilemma, and while they were booked, they did have room in their overflow area. Erica and I could have hugged her. We left Jake. The woman who took in our dog thought it was so cute he brought his own tennis ball in his mouth.

For our visit to the nation’s capital, we endured record breaking heat and humidity. One night while we ate chili sitting at the picnic table of our campsite June bugs fell like intermittent rain from the sky. When I bit into one of the crunchy critters that was the end of my meal. Erica stopped the minute the first bug fell. Another day while our truck was parked in a gated metro parking lot we were robbed of our cd collection, speakers, and a 35 millimeter camera. In the meantime, Jake enjoyed air conditioning, music while he slept, and runs outside with his companions. When we picked him up the boarders couldn’t stop talking about how much they loved Jake staying with them. He hinted of a weekend retreat while we felt like we had just crawled out of a dumpster.

It was not hard to see Jake was born of a generational lineage to hunt birds. I had never hunted before going with August, and his dog, Tasha. Erica’s father has hunted most of his life. If he wasn’t hunting then he was fishing. Tasha, a smaller lab more white than yellow in color, was the lead huntress. It didn’t take Jake long to tap into his heritage. Yet his excitement when he first entered a field required patience. A thirty-to-forty-five-minute wait for him to settle was routine. In those fields he was like a child bursting through the gates of Disneyland. He always moved in hunting patterns, but at a quickened pace that didn’t produce a bird. Once he was more relaxed he got to the core of who he was.

It took close to six months before I settled on Jake’s name. For a few months I called him JD. It was a ridiculously cliched name. Jack Daniels wasn’t even my favorite whiskey. I’ve always been a Wild Turkey man. It didn’t stick. Erica, on a shout out to The Jungle Book, recommended Baloo. We tried it for a while then my roommate asked, “Your dog’s name is Bluuuuuue?” as if it were an ancient word he had never heard. My dog didn’t need that kind of confusion in his life. On a trip to Chico for a wedding Erica and I drove past a litany of bars and restaurants. Among those was Jake’s Bar. While visiting friends I had been in a few times. They had sawdust on the floor.

When the girls were born, we felt it best to be close to family. That put us in a two-bedroom apartment near our parents. For two years Jake lived with August, Louise, and Roger. Her brother was just finishing high school. He taught Jake to bark when asked if he wanted a beer. There my dog became a menace to the neighbors by stealing newspapers and swimming in their pools. When Erica and I bought our first house I vowed I would never give up my dog again.

It’s difficult to believe Jake only lived three and half years in Birchwood. Of all of us I was most happy for him. No longer would we have to walk among the walnut orchards down the street in a pathetic attempt at simulating hiking in the woods. Twice, in the dark of evening, we stumbled across a skunk that sprayed us. Erica was so happy when we returned home.

In the Adirondacks we hiked miles of trails near Birchwood. From our store it was an easy walk to the woods. Behind the school we climbed Pine Ridge, past the water tower and the rusted out vintage truck that powered the rope tow for skiers during the thirties. The other side lead to Rondaxe Mountain. Those were the longer hikes. For a quicker two mile jaunt my last four dogs have hiked the Middle Branch trail to the dam.

Jake liked to wander. His social skills were not about attention. They were a ploy to get what he wanted most, people food. In a pattern only he knew Jake would hang around the property without supervision for weeks, sometimes months. Then without warning he would be gone. Often days at a time. Many times, while searching for him at night we’d find him at the lumberyard. He’d either be locked up behind the chain link gate, or behind the glass of the store’s entrance. It was his own fault. To get locked inside he would visit the general manager’s office during the day. He’d sleep there for hours, and Maeve would forget he was there when she closed. Then there were the visits to the Old Birchwood Hardware store.

He must have gotten in through the back because no one saw him come through the front. There, the stairs off the loading dock lead inside. A door must have been left open. Which wasn’t a problem because the owners were dog friendly and allowed them in their store. I’m sure people mistook him for just another big goofy dog. They had no idea the cunning intellect they were dealing with. Unknowingly their attention to him with back scratches and pats on his head encouraged his thievery. His goal was the bin of pig ears. I know he didn’t think it was a problem when he grabbed one and tried to follow his path back outside with it. This happened more than once. Erica took more angry calls from the manager than I did.

“We like having dog’s in here, but we can’t have them stealing,” the manager scolded Erica when she went to pick up our criminal and pay his five dollar bill. I understand, she said, leading Jake out of the store. The embarrassment was her own, as our hoodlum was too cocky to care.

His travels gained him recognition. A handful of times when friends introduced me and, or Erica to other locals we’d get a puzzled look. Like our story wasn’t adding up. To clear up the confusion our friends would add this is Jake the dog’s, mom and dad. Their faces always lit up in joyous recognition. I know Jake. I love that dog, they would say.

For two weeks I put off the inevitable. The day of his appointment the temperature was a sharp ten degrees below zero, and the sky a cloudless baby blue. During Adirondack winters those are the sunniest, brightest, and cruelest. I lifted my dog onto the second row of seats in Erica’s SUV. By then Jake’s eyes were cloudy, the arthritis in his hips caused him pain, and made him unstable. He was also deaf, which was a concern when he wandered through town, and across the highway. Route 28 is a two-lane road with a speed limit of 25 m.p.h. in town. Despite our best attempts, Jake found ways to get out of the house, and wander. Even now there are not many fenced in yards in Birchwood. All four of us knew we couldn’t get mad at him. Wandering was as much about Jake’s nature as breathing.

It didn’t matter whether it was the bitter cold of winter, or the hot humid days of summer, Jake had to be who he was. Our acceptance of his nature didn’t make being his owners any easier. Countless nights we drove around looking for him when we should have been in bed. We were rarely successful in bringing him home and would have to resign ourselves to waiting for his return. There was always the worry he would get hit by a car. Jake treated his passages over busy roads with the same casualness he did for crossing a yard. What if he froze to death in a below zero night? What would this small town, where dogs are part of the community’s soul, say of owners who let their dog freeze to death?

At that time, I thought of him as an alcoholic dog. At home he would promise to stay on the property, but then the thirst of wandering would be too great, and he’d walk off. Many times for days, as if he were binge drinking. Until his body couldn’t take anymore abuse, and he’d return home. Each time, we so wanted to believe he had finally learned his lesson and turned the corner. His returns brought throwing up, diarrhea, scrubbing on hands and knees, and a half dozen carpet cleanings. Just over the bridge we turned onto Fenimore River Road. The river flowed strong, treacherous. During the summer it was lower, calmer. Along one of its many bends we passed an eddy between two large rocks just off the shore that was great for trout fishing. It took me back to the only time Jake swam in the ocean, thirteen years before. Erica and I were on our cross-country trip. Back then, Marc and Anne lived in Virginia Beach. Marc was an officer in the Navy. They, like us, had married in the previous year.

While Marc worked at protecting our country the rest of us sought refuge from the sweltering heat of Virginia in July with a trip to the beach. Despite Anne tugging on Apollo’s leash, their Alaskan Malamute mix, would not go anywhere near the crashing waves. The two of them in a stalemate reminded me of a Norman Rockwell painting. Jake had no reservations. He threw himself into the water with the joy of a child. Against the crashing waves he puffed up his chest and swam out to retrieve his tennis ball in calmer waters. Coming in he swam until catching the momentum of a wave. Then, using his tail like a rutter, he would surf in to shore. I wore out my arm throwing the ball. His happiness made us all happy that day. Everyone, except Apollo that is.

We followed Highway 12 north before pulling into the veterinarian’s parking lot. By then my frail sidekick of fifteen years had lost his muscle definition. Left behind was his coat that hung on his bones like a rumbled rug. He was deaf, and nearly blind and didn’t have the strength to care. I thought of how many times I had cleaned the carpet to stop myself from breaking down.

I put the leash on him. It had been a long time since I had. Jake understood that as long as he followed my commands, he would be given freedoms he would not otherwise get. On the same cross-country trip that took us to Virginia, we stopped at the Garden of the Gods in Colorado Springs. In that public park he went from being a boy to a man.

He was two years old, and still finding himself. Erica wasn’t feeling well so she stayed at the truck while Jake and I hiked the park. Initially I kept him on a leash as we traversed the rocks, shrubs, and pathways. Garden of the Gods is like a giant natural jungle gym. We hiked everywhere. I was as excited as he was to run around that place. Soon our attachment with the leash became cumbersome so I unhooked him except when we were on the path with other visitors. Then that became a burden. Jake was always friendly, and social, and it was not beyond him to visit people and dogs. But on that hike, he couldn’t have cared less about anyone except me and him. Without the leash we moved like one. Step by step in sync with each other. Verbal communication turned to intuition. I didn’t have to say a command.

We slowly walked up the ramp and into the receiving room. A woman standing behind the counter asked with compassion, “Is that Jake?”

“Yes.” She handed me forms to sign.

“Go ahead and take a seat and we’ll be right with you,” she instructed.

The waiting room was L shaped with a bench running the length of it. I walked us to the furthest corner, nearest the bathroom. A guy, who was probably only a few years older than I am now, sat near the middle with his elderly terrier. “That dog seems as old as mine.” I didn’t respond as I tied Jake’s leash to the bench before using the bathroom.

Not long afterward a nurse approached and led us into an exam room. We waited nearly twenty minutes. Jake stood, but quickly his legs shook from weak arthritic hips. He lay on the floor. There was a strain in his raspy breath. I heard footsteps before the back door opened. In walked two women. The young short haired brunette, petted Jake, and moved behind him. The vet knelt in front, put a small tray on the floor, and petted Jake’s face and ears. Jake slowly sat up.

“Have you had him a long time?” the woman to his rear asked.

“Almost 15 years” I said kneeling next to him.

“Is he in poor health?”

“Yeah,” I said. “He barely eats. He’s completely deaf, and I think he has dementia. He’s also lost control of his bowels.”

“Fifteen years is a long time for a dog his size,” she said sympathically.

“Have you been through this before?” asked the vet.

“Yes.”

“What I’m going to do is give him an overdose that will make him unconscious then stop his heart.”

“Ok,” I said with a voice barely above a whisper. I could feel the tears start to well, and my nose started to run.

The vet pulled a syringe from the tray and stuck it in a vial. Jake was still sitting up. “It would be better if he lay down.”

Initially I let them try to get him to lay, but he refused. I rubbed my face against the side of his, while using my other hand to scratch his back. “Cmon Jake,” I said. “Lay down, buddy. I love you. It’s going to be all right.” Slowly he went down.

With his front legs extended the vet swiped his right leg with an antiseptic then steadily inserted the needle, pushing death into his body. I rubbed his neck and ears and told him it was going to be all right. Tears rolled down my face and my nose ran, but I was not about to let go of my dog. Just before his head became too heavy for him to hold it up, he turned and looked at me. In his clouded eyes he was a confused, broken dog. I sensed he felt like I had broken a trust between us. Of course, it was the right thing to do, but it didn’t mean my heart wouldn’t be broken. Jake closed his eyes and lay with his head down. His breathing slowed, and there seemed to be a peace about him. The vet reached for her stethoscope and placed it against his body. “He’s unconscious now,” she said. “His heart is still beating though.”

“He was always stubborn,” I said.

Then she said, “His heart has stopped beating.”

I stood up and sat on the chair in the corner. I couldn’t stop crying. The depth of my grief was more than I expected. I looked at him lying on the floor, and he was just a body. His spirit, his essence, gone forever. I felt empty.

“I’m so sorry for your loss,” the vet said before leaving the room.

“Thank you.”

“You can stay with him awhile if you would like,” said the assistant.

I stood. “Is there anything else I need to do?”

“No,” she said, “we’ll come back in here in a few minutes and take him out.”

She stood near the cabinet. “Can I have a tissue?”

“Sure,” she said. She grabbed a box of tissues and handed it to me.

I blew my nose and wiped my cheeks with the sleeve on from my hoodie. It would be the most composed I would be. I had to get out of there. “Thank you,” I said moving toward the door that led into the lobby. “So, we’re done?”

“Yes,” she replied. “But you can stay with him if you want.”

“No, that’s ok,” I said taking a last look at my lifeless companion on the floor.

Quickly I walked into the lobby and headed for the front door. It was all I could do to hold back the wave of sadness I felt coming over me. I kept my head down. In the SUV I poured out every feeling I had for Jake. I knew it was the right thing to do. I knew the decision was a quality-of-life issue. I knew the entire family was tired of cleaning up after him. But then he was gone, forever. I would never get to wrap my arms around him, bury my face in the scruff of his neck, and let him how much I loved him.